skip to main |

skip to sidebar

The Caterpillar took the hookah

from its mouth and said:

"WHO are YOU?

What do you do?

Are you happy or blue?

False or true?"

Alice answered:

"I hardly know, sir...

my life's in a whir,

my mind is a blur,

I've not a dollar nor a diller.

So pass that hookah, Caterpillar,

or I'll crush ya, that's for sher."

*~*~*~*~*~*~*

"Caterpiggle wiggle

You sure are plush

Think I'll sit on you

*~*~*plants her tush*~*~*

So whatz yer vision?

Whatz the vista?

Fill this hookah

Wontcha mistah…"

*~*~*~*~*~*~*

"Cracked my head

open. Colored rain

Fall'd skyward from

My swirling brain.

In a minute

Knew it all

Now you kin, Alice

Though yer small…

But one puff

is definitely not enough"

*~*~*~*~*~*~*

Alice said:

"Be quiet, bug,

Don't push yer drug,

You plushy lug.

I'm saving room

for the 'shroom.

Then I'll ZOOM.

Wmmvrrvrrmmmvvrrvrrvrrrrrrrmmmmm..."

*~*~*~*~*~*~*

"Hmm I see,

my Alice chile,

what's behind

that dainty smile…

'Shroom indeed,

but for that

yewl have to see

the Cheshire Cat.

Two puffs then

before yer gone

from me silly

billy bong…"

*~*~*~*~*~*~*

"Oh fuzzy one, yer really trippin',

perhaps you should slow down a bit?

I mean the 'shroom on which we're sittin',

me on you and you on it.

From nibblin' this mound

I could get taller or smaller

dependin' on which side,

and thass a toughie, 'cause, you see,

it's perfectly round.

Whatevah--it'll be a wild ride!"

*~*~*~*~*~*~*

"Harrumph! Yes well

I might have tripped

I wasn't told

There was a script

How queer indeed

Your words be true

A mushroom sure

as I am blue…

Must be the Cheshire kitty lied

Or then like now I wuz too fried

So psilly fungi's a magic seat

From which side will you eat?"

*~*~*~*~*~*~*

"Which side shall I eat?

Thass tough, as I said,

It's so round a seat

with, really, no sides,

it boggles my head

but it's time that I tried..."

(Alice stretches her arms around the

'shroom as far as they will go, and breaks

off a bit of the edges with each hand. She

nibbles a bit of the right-hand side...)

"OOF! my chin's on my foot! this is not goot!"

(She tries a bit from the other side.)

" OOPS! my head's in the sky!

Well, I DID want to get high..."

And

Alice continues on with her adventures, leaving the Caterpillar

peacefully smoking his hookah--one last party before entering the

darkness and stillness of cocoon-time, where no smoking is allowed.

Instead, the Caterpillar will dream constantly, in vivid color - X-rated dreams of butterfly love...

“Then take me disappearing through the smoke rings of my mind …”

Bob Dylan, “Mr. Tambourine Man”

In numerology, the number five represents the energy of adventure, freedom, and change, and the fifth chapter of Alice in Wonderland is rich in the symbolism of far-reaching transformation. It is said that God must be a mathematician; he may also be a numerologist, and just may be symbolized by the Caterpillar, cozily ensconced on a mushroom, smoking his hookah and lording it over those who, like Alice, are seeking answers. He, too, seeks one: “You! Who are you?” In this, he may represent consciousness itself, which is continually asking us to define our identity. A change in consciousness may require a period of land-locked, fuzzy caterpillar-creeping, followed by sequestering in a chrysalis, before taking flight as the “butterfly” of a new and glorious manifestation. The Caterpillar takes a cavalier attitude toward Alice’s perception that such a transformation is “strange,” implying that he’s accustomed to it.

Of course, normal caterpillars go through this only once.

Marc Edmund Jones, in his "Studies in Alice" at www.sabian.org/alice.htm, sees the Caterpillar as symbolizing the inner self: “The real or inner self is symbolized by the worm. … Observe the development of the primal streak or wormlike beginning of differentiation in the embryo. … The convenient symbolism of the inner self is further borne out in the fact that the true butterfly does not eat, but exists through the whole span of its existence, aerially or spiritually or in beauty, on the vitality it has stored up in the worm state.” This also applies to the metaphor of the butterfly as the fulfillment of an idea that has undergone incubation and is then realized in form, living on the power that has built up around its “inner self” in the womb of thought, through the time of gestation. Jones goes on to address the symbolism of the mushroom seat, pointing out that the endocrine glands are the “mushrooms” of the body because they are symbionts that exert much power in relation to their environment. “That a caterpillar should be seated on a mushroom is itself a remarkable bit of inspirational imagining, and that one side of this mushroom should cause Alice to grow and that the other should reduce her in stature is so perfect a picture of the functioning of the anterior and posterior lobes of the pituitary body as to make Alice in Wonderland forever immortal as an achievement in symbolism. Growth and its lack, especially in stature, … is controlled entirely by these two lobes in counterbalance.”

The Caterpillar’s mushroom seat and hookah-smoking have often been taken as one of the indications that the Alice books were inspired by some kind of hallucinogenic drug, or, at least, that Carroll was familiar with them. Although it is highly unlikely that he ever used these substances, Carroll was an inveterate reader and explorer of many areas of life, especially of the occult (he owned a copy of Stimulants And Narcotics (1864) by the English toxicologist Francis Anstie), and it is possible that he had some knowledge of them. Even if so, it is doubtful the subject held much personal interest for him, since he was quite conservative, even ascetic, in his habits, although progressive in his thought. Migraines and temporal lobe epilepsy have been suggested as contributing to his unusual imagination, but here, too, the facts are inconclusive. In any case, he demonstrated a superb, wide-ranging imagination throughout his life, as well as a highly developed spiritual awareness that went far beyond the dogma of his church.

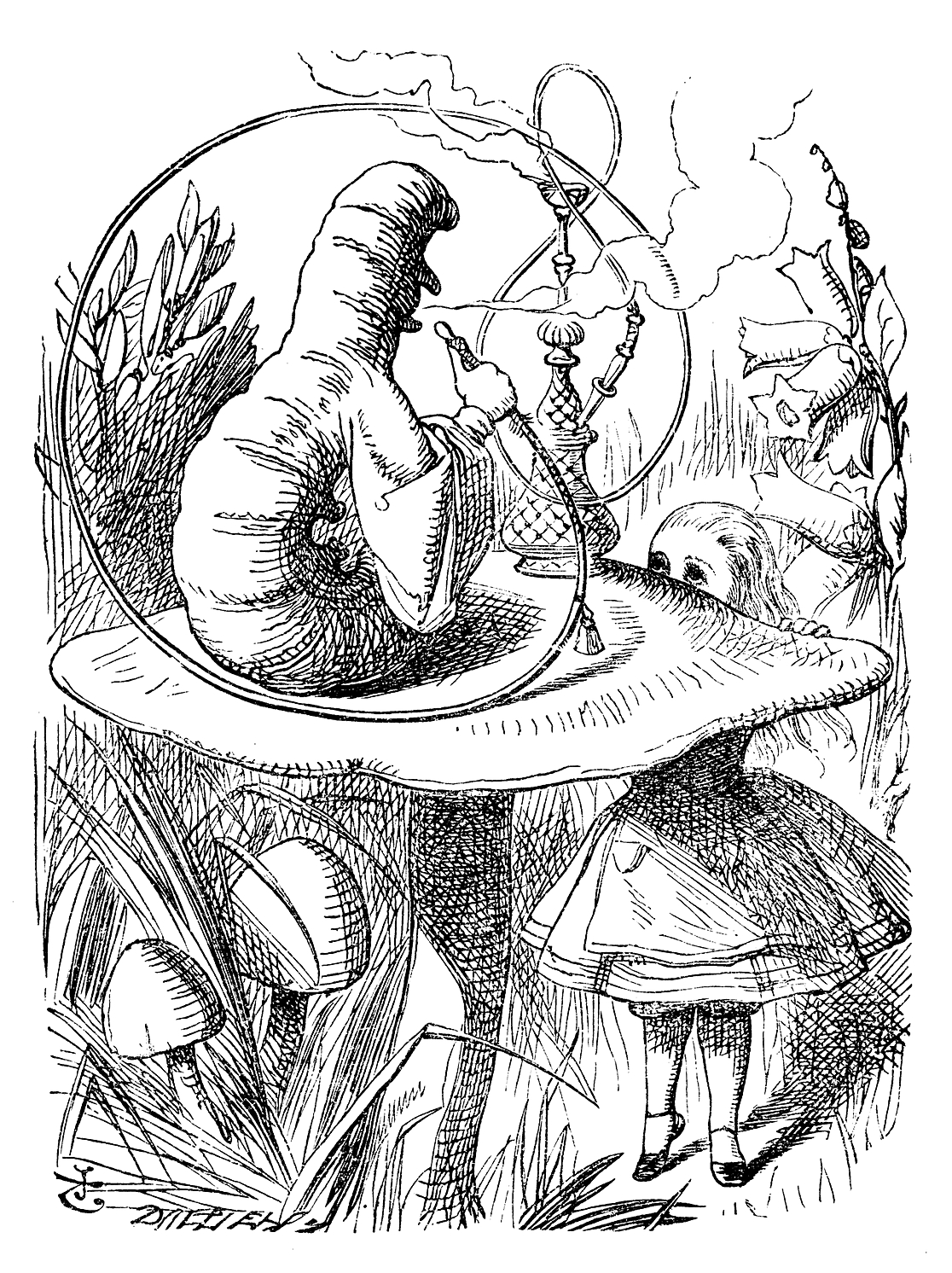

Although psychedelic experiences are often facilitated by psychoactive drugs, they are not required. The word “psychedelic” means “mind-manifesting,” and the psychedelic experience, as noted in Wikipedia, “is characterized by the perception of aspects of one’s mind previously unknown, or by the creative exuberance of the mind liberated from its ordinary fetters.” In this broader sense, the two books can be seen as psychedelic literature, and Tenniel’s tableau of the Caterpillar sitting on the mushroom smoking a hookah, with Alice peeking up at him just behind the mushroom, is a powerful archetype of transformation.

The hookah may be the most arresting aspect of that tableau (what was that Caterpillar smoking?). Continues Jones: “The hookah, an arrangement to pass smoke through water, is an added touch of unwitting genius, for the endocrines alone make possible the entrance of spirit or smoke into sensation or water.” Natives of aboriginal cultures, including American Indians, have long used tobacco to connect to the divine realm and to the Great Spirit.

Swiss anthropologist Jeremy Narby set out to discover how, out of the many thousands of plants growing in the Amazon rainforest, the natives had learned which of them had medicinal properties and how best to combine them. He was told the information came from the shamans when in altered states of consciousness. In The Cosmic Serpent: DNA and the Origins of Knowledge, Narby explores the shamans’ use of high-nicotine native tobacco and other, ingestible plant substances such as ayahuasca and psychoactive mushrooms. In altered states of consciousness, they can “take their consciousness down to the molecular level and gain access to information related to DNA, which they call ‘animate essences’ or ‘spirits.’ This is where they see double helixes, twisted ladders, and chromosome shapes. This is how shamanic cultures have known for millennia that the vital principle is the same for all living beings and is shaped like two entwined serpents (or vines, ropes, ladders). DNA is the source of their astonishing botanical and medicinal knowledge, which can be attained only in defocalized and ‘nonrational’ states of consciousness, though its results are empirically verifiable.”

Narby hypothesized that properties of nicotine or the psychoactive plants used by shamans “activate their respective receptors, which sets off a cascade of electrochemical reactions inside the neurons, leading to the stimulation of DNA and, more particularly, to its emission of visible waves, which shamans perceive as ‘hallucinations.’ … There, I thought, is the source of knowledge: DNA, living in water and emitting photons, like an aquatic dragon spitting fire.” He theorizes that photons are visible as light signals that communicate information from the DNA cell to cell. Scientists do not know the function of 98 percent of our DNA, which they term “junk DNA”; Narby suggests we call it “mystery DNA,” and theorizes that our collective DNA is interconnected and in constant communication.

The information the Amazonian shamans received was not confined to botanical knowledge, but incorporated into the learning of necessary skills such as weaving and woodworking. In fact, anything the natives wanted to know was accessible through the shamans. Narby hypothesized that the symbolism of the snake, a constant in the wisdom traditions throughout history (often accompanied by the Tree of Life or a Caduceus), is connected to the double helix of DNA in almost all living beings—this, despite the fact that conventional science did not discover the existence and structure of DNA until 1953. He cites various Cosmic Serpent creation myths, such as that of the plumed serpent Quetzalcoatl, and refers to our DNA as a master of transformation: “The cell-based life DNA informs made the air we breathe, the landscape we see, and the mind-boggling diversity of living beings of which we are a part.” After Alice ingests some of the mushroom and finds that she is able to bend her neck around like a snake, she encounters an angry pigeon who shrieks that Alice must be “a kind of serpent.”

The transformational features of the mushroom also have a historical meaning, though not one that you’ll find in many history books. Ethnobotanist and “psychonaut” Terence McKenna put forth, in his book Food For The Gods, the theory that psychoactive mushrooms were a crucial catalyst in our rapid evolution. The human brain size tripled over several million years; the hallucinogenic compound DMT (di-methyl-tryptamine), found in the the mushrooms and other plants used by shamans, is one of the chemical factors that McKenna theorizes played a role: “We literally may have eaten our way to higher consciousness.” DMT is also naturally produced in small amounts in the pineal gland, notably in deep dream states and at birth and death. Few books convey deep dream states as well as the Alice books; those who insist that Carroll’s works are the products of drug experiences may be sensing this dream chemical wafting through their pages.

Throughout her dream-adventures, Alice struggles with the epistemological question of whether her experiences are real. Are our dreams and other altered-state experiences any less “real” than our waking life? Writes Rick Strassman in his book DMT, The Spirit Molecule: “The other planes of existence are always there … but we cannot perceive them because we are not designed to do so; our hard-wiring keeps us tuned in to Channel Normal.” Rather than seeing these other planes as pure hallucination, Strassman accepts them as realities that we tune in to when in these altered states.

Psychedelic mushrooms are also called ethneogens, a term meaning “creating or becoming divine within.” The yogic headstand is perhaps another such tool. Alice’s rendering of “You Are Old, Father William” is the first instance of a character “incessantly” standing on his head; this is also a favored, though less deliberate, posture of the White Knight in Through The Looking-Glass, who assures Alice: “The more head-downwards I am, the more I keep inventing new things.”

Most babies face head downwards in their final weeks in the womb; “inventing new things” can be taken as a metaphor for any kind of birth or new beginning. We naturally transform our world when standing on our head, both perceptively and on inner levels, through action on the glands, particularly the pineal. The Hanged Man, hanging serenely upside down from a tree in the twelfth card of the Tarot, is an archetype of this transitional and transformational process, and the Caterpillar itself, like all headed for butterflyhood, will hang head downwards as it transforms within its chrysalis.

According to the insect biologist Carroll Williams, in an article titled “When Insects Change Form”(Life, February 11, 1952), a caterpillar’s transformation is triggered by a hormone in the brain which, in turn, stimulates the thoracic hormone in the region of the heart. This “forces the body cells to produce a substance called cytochrome, which hastens growth and change. … This same cytochrome exists in the cells of the human body, but its role as a growth factor has never been known.” Along with the 98 percent of our DNA that seemingly has no function, it could be that this cytochrome substance is far more crucial than we know.

Is it possible that the Absolute has been cocooned in us, waiting for the right time to awaken fully in our hearts? Is this what we will experience in the future—or now, if we can but invoke it—and will the Caterpillar of our collective "inner self" flutter free of its cocoon, utterly transformed?